Part 1: The Park

This winter’s trip to Yellowstone was a rewarding experience in terms of the abundance of wildlife, steamy landscapes and record breaking cold (lowest temperature was -56F)…

As the world’s first national park, a visit to Yellowstone in any season does not disappoint, but it is in the winter, when the temperatures typically drop to the lowest levels anywhere in the lower 48, that the park’s ecology and geology shine the brightest. And this trip, from an overall, top to bottom perspective, has been my most productive expedition in the last year.

In terms of my all-time favorite subjects, bears are still tops. But when I go on a bear-centric trip, it is such a demanding subject (physically and mentally), there is little room for much else…this was not the case in Yellowstone. This park does have its specialties, and I could have gone with a single focus, but, in my opinion, and at this point in my career/catalog, it is best enjoyed by thoroughly absorbing as much of the Yellowstone experience as possible.

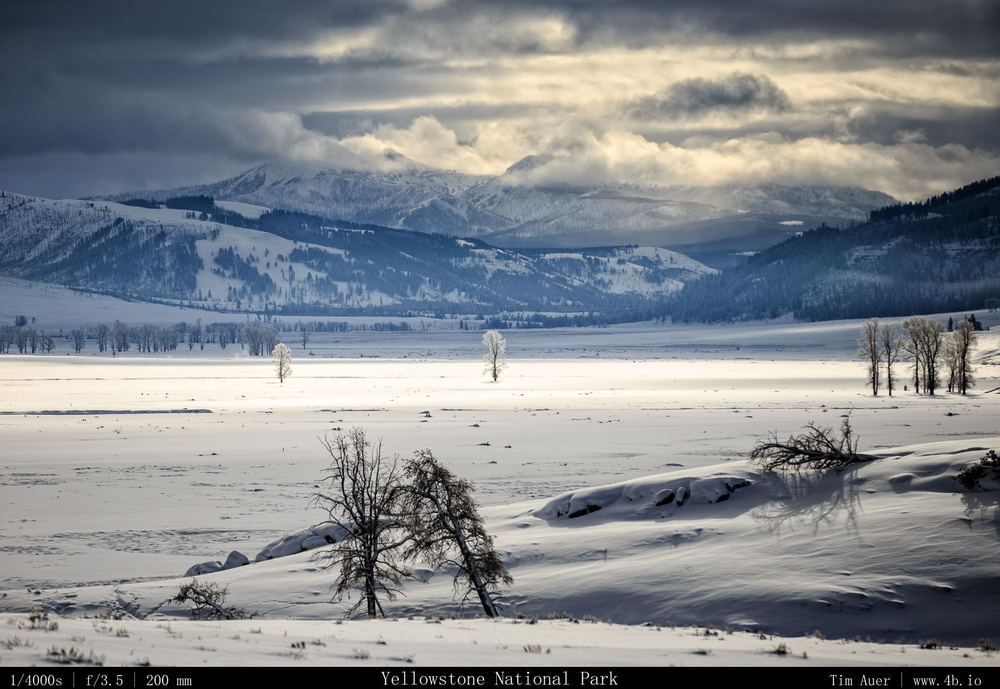

The park, renowned for its abundant wildlife and extensive geothermal features (most extensive in the world), has at times been faulted for lacking the iconic vistas that define some of the other US national parks, such as Yosemite or Glacier. However, the ecological variety and ever-changing geothermal landscapes creates iconic scenes that may only last a moment. The trick is to be at the right spot, at the right moment to witness it.

Yellowstone is different, while it is true the famous views such as “Snake River Overlook“, “Gates of the Valley” or “Wild Goose Island” are not there, fleeting but profound images can be wrought from the Yellowstone landscape. And it is because of the fleeting nature of these scenes that make the resulting image more profound; it serves as a reminder of the Earth’s transient nature. In the words of Paul C, our snowmobile guide, the only constant in Yellowstone is change. On a geological scale, this is universally true everywhere, the earth’s surface is in constant flux. But on a human scale we rarely have the opportunity to witness this geological ballet. Yosemite Valley in California looks much the same now as it did when Ansel Adams first visited in 1916. Yellowstone on the other hand, with its massive magma chamber bubbling a scant 3 or 4 miles beneath the surface, changes noticeably on a daily basis. These types of geological changes to the earth are most apparent here than anywhere else in the world.

More so than most of the other parks, Yellowstone exercises all of the human senses. A photographer, who attempts to use imagery to communicate the Yellowstone experience is limited to the visual cues presenting. Many of the scenes contain stimuli that require a first hand encounter to understand and appreciate. Therefore, I tried my best to capture visual scenes that offer connections to your other senses…this is easier said than achieved…

What these photographs fail to capture and present to the viewer is the frigid air, the smells, the sounds, the rumbling, the vibrations, the mists, the howls, the grunts, and the silence that are uniquely available in Yellowstone, the most accessible of the snowbound American National Parks. While other of the snowy Parks have generally limited access during the winter, Yellowstone’s hundreds of miles of roads are almost fully accessible via snowmobile and snow coach while the northern section (Mammoth Terraces and Lamar Valley) is plowed and open to cars.

Next up….

YNP P2: The Wildlife

YNP P3: The People