Update May 2017

A few weeks ago, when I heard the death of the 12 year old Canyon Alpha female, I held hope her injuries had been natural, not due to man. My disappointment was palpable when I learned she had in fact been shot. The bullet didn’t immediately kill her. The shooter only managed to fatally wound her. She still clung to life but, after surviving 12 years in Yellowstone’s unforgiving wilds, she was euthanized due to the injuries. Nature is brutal and a comfortable death is not expected for a wild animal, but it is a shame how this iconic wolf met her demise.

As the first wild wolf I ever saw, alongside her longtime mate, the Canyon pack Alpha female held a special place in my heart.

See below for album that includes photos of the White she wolf of Canyon Pack.

Dogs of Yellowstone: Wolves and Coyotes

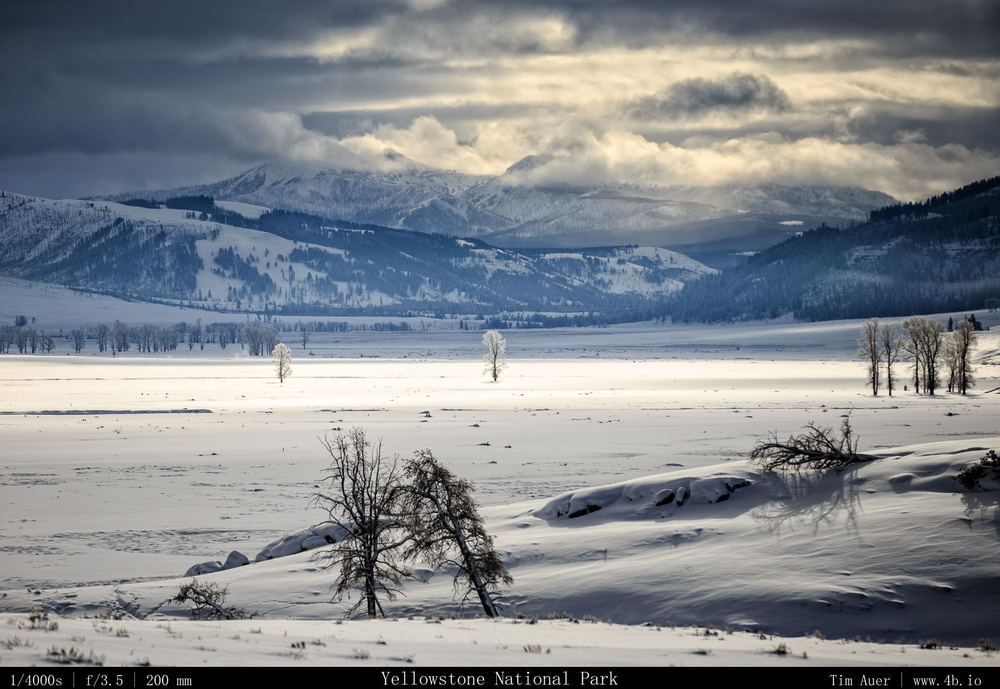

I had several first time wildlife encounters on this trip. At the top of that list were wolves. A wild wolf is not an easy animal to see in its natural habitat. In fact, the primary goal of last year’s winter trip to Yellowstone was for wolf photography, and I didn’t see a single wolf on that trip. It serves as a costly but useful reminder that in a wild place, the wildlife are in charge. And that you need to adjust your approach to increase the likelihood of success of finding a given animal. Fortunately, this trip was different, not only did I see wolves, I saw lots of them. A lot of that had to do with spending more time in the Lamar Valley, having a vehicle, making better connections, and weeks of research to prepare.

Not only are wolves difficult to spot, they are even more difficult to photograph. As an intelligent and alert species, they are naturally wary of humans and keep their distance. On top of that, the wolves weren’t particularly active when the light was abundant. In fact, most of my sightings were in the hour before sunrise and the hour after sunset. In other words it was usually dark out when I saw them. I was forced to shoot with my lens wide-open and push the ISO to 1600, 3200 and in some cases 6400. The rest of the trip I was rarely above ISO 100.

But the first wolf encounter is something that resonates deep inside the human animal. Before seeing them, you first hear their howls. Long, deep cries that carry over long distances. Echoing through the valleys and off the mountains in the dark and cold morning twilight. The sound is primitive and shivering to the spinal column. The cries are answered by other wolves, but its not clear where they are. You know the general direction in which the sound originated, but it is difficult to pinpoint an approximate location. All you see are trees, snow, and shadows, each which is fair game for the wolf. And then all of a sudden out of the corner of my eye, and not in a location that I expected, a gray wolf is seen bounding through deep snow across the top of a ridge with another wolf following….

The day (my second in the park) was off to an exciting start! Not only had I seen my first wolves, but the previous day was productive, yielding many usable photos of bison, elk, sheep, and coyote. Well it turns out that the highlight of Day 2 was seeing the wolves at sunrise. The weather was windy and snowy for most of the afternoon, of all the animals in Yellowstone that day, it was the wildlife that seemed to have better judgement, by staying bedded down all day. There were barely any bison to photograph. Later in the day, we became aware of an injured bull elk on a cliff overlooking Soda Butte. It was reported that wolves overnight had ripped open his left rear leg and backed him into the cliff. The mortally wounded elk managed to fight off his attackers through the night and remained on the cliff, alive, till the following afternoon. It is not clear why the wolves left their prize unattended. Likely the elk’s antlers behaved like a bayonet, and gave him the advantage in the cliff’s close quarters. But the wolves, as is often the case, appeared to have a plan and weren’t gone for good. In fact, it was like they simply “put the elk in the fridge” and would return at a less risky time, after he had bleed out.

Later in the week, we got even closer to the Canyon pack between Mammoth Hot Spring and the high bridge heading out towards Lamar. We tracked a lone gray wolf with a bloodied throat along a ridge by Blacktail Creek. It was making its way back and forth across the road. It was not clear if the blood was from feeding or its own. Afterall, it was the start of mating season and this lone wolf may have been injured by the pack’s alpha male. Lastly, on this day we were fortunate to see a pack of wolves, including two coupled alphas on the start of mating season. This pack was seen over 2 miles away, and the photo of this included here was on 1200mm focal length on a 1.3x crop body, giving 1560mm of optical reach, furthermore I cropped it by 100%, which means the equivalent zoom on this photo is approximately 3120mm. A lens of this size would be extremely difficult to handhold, as it would probably be 10 feet long and weigh up to 500 lbs. The wolves were far and it goes without saying this photo has minimal photographic merit. I just thought it was interesting to have a single photo of 7 wolves.

Coyotes are quite prevalent in Yellowstone in winter, frequently misleading visitors into thinking they have spotted a wolf. As you can see by two of these photos, some coyotes suffer severe cases of mange and have lost significant amounts of hair. This an extremely uncomfortable and possibly deadly disorder for these animals when the temperatures drop to -56F like it did during our visit there.

Here is a huge dump of the various “dog” photos from Yellowstone….